Beyond The Chador Regional Dress From Iran

4. Kangas from East Africa and India

Kangas are large, rectangular cotton cloths (c. 150 x 100 cm) that are brightly coloured and have a distinctive, printed text. They are worn by women living along the east coast of Africa, especially in Kenya and Tanzania. Kangas are also worn by some groups in Oman, due to long standing, historical connections between the various countries.

Kangas and similar garments have been part of the East African, Swahili dress code since the late 19th century. Throughout the decades kangas adopted textual and decorative elements from Arab, African, European and Indian sources. The garments are regarded as an essential item of a woman’s wardrobe and are worn on a daily basis in and around the home and outside, as well as on important occasions such as weddings and funerals.

Their designs, colours and texts are not static. They are constantly being modified and adapted to the current economic and political situation, as well as customer demand. The designs on older kangas were made locally or in India, with hand printing using large, wooden blocks. More recent examples, however, tend to be machine printed using a system of rollers. The modern versions are usually made in Tanzania and Kenya for their local markets. Examples from India are sold in Oman as well as in East Africa, but they are not as highly valued, as both the cloth and designs tend to be of a poorer quality.

Kanga designs and messages

The kanga cloths are normally bought in pairs. They always have a decorative border (pindo), and a different pattern in the central panel (mji). The main patterns range from simple geometric shapes to depictions of locally important buildings and events. The distinctive feature of the kanga is the saying (jina), printed along the lower edge of the central panel. Most of the sayings are in Swahili, the common language of East Africa. In the older versions, however, these sayings were written in Arabic script, more recent ones, however, normally use Latin script. Occasionally sayings in English can be found, but these are generally intended for the tourist market. All of the sayings contain messages about friendship, love and politics. In fact, they may refer to just about anything.

How are they worn?

Women use the kangas in various ways: for carrying their baby on their backs, as a general wrapping around the body, and as sheets at night. When worn as clothing, one kanga is wrapped around the body at chest height in order to cover the breasts and lower part of the body. The other kanga is draped around the head and shoulders, acting as a modesty veil. Nowadays, kangas are sometimes made into a blouse and trouser outfit.

3. Indian George and Madras textiles

For centuries a popular type of textile used by the Igbo people in Nigeria is called ‘George cloth’. During the 20th century this type of cloth became popular among a much wider group in Nigeria and among Nigerians living elsewhere in the world. In the Netherlands it is known as Madras cloth. While many know that the cloth originates from India, the question remains: what exactly is ‘George’ or 'Madras' cloth?

It would seem that there is no consensus concerning exactly what makes a Nigerian George cloth. Sometimes it is described as ‘plain George’, while other forms are known as ‘fancy George’. There are also checked (tartan, plaid) Georges with embroidered squares, plain Georges with gold coloured thread woven into it, not to mention embroidered Georges with floral motifs using sequins and mirrors.

This is the beginning of the huge international trade in what became generically known as Madras cloth or Madras-doek in the Netherlands. The story continues because the Dutch took Madras cloth to their colonies in the Caribbean and West Indies, including Surinam and Curaçao. This type of material is still known in the West Indies as Madras.

2. Medieval Indian textiles from Quseir al-Qadim in Egypt

For hundreds of years India has been exporting textiles to the east coast of Africa, and hence onto the eastern Mediterranean via the Red Sea. During the Roman period, for example, Indian cotton textiles found their way to the Red Sea ports of Berenica and Myos Hormos, later known as Quseir al-Qadim. The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a shipping manual written in Greek during the mid-first century AD, provides information about the type of goods, including textiles, that travelled to and from India, East Africa, the Red Sea and the Arabian Peninsula.

Fragment of medieval cotton textile from India, excavated at Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt, in early 1980s (TRC 2020.0245b).Quseir al-Qadim was a busy port during the Roman period and contemporary Indian cotton textiles were found at the site, but when the economic conditions declined in the 2nd century the port of Quseir went into decline. A thousand years later however, the Egyptian economy was once more booming and the port was active for about another 150 years.

Fragment of medieval cotton textile from India, excavated at Quseir al-Qadim, Egypt, in early 1980s (TRC 2020.0245b).Quseir al-Qadim was a busy port during the Roman period and contemporary Indian cotton textiles were found at the site, but when the economic conditions declined in the 2nd century the port of Quseir went into decline. A thousand years later however, the Egyptian economy was once more booming and the port was active for about another 150 years.

During that time, in the 13th and 14th century, Quseir al Qadim also saw the import of cotton and silk textiles from western India. Some of them were transported to southern Egypt and were found at medieval sites such as Gebel Adda and Qasr Ibrim.

Other textiles were moved northwards to Fustat, the capital of Egypt at that time and now a suburb of modern Cairo. The TRC Colleciton includes fragments of these medieval Indian textiles, discovered at Quseir al-Qadim in the early 1980s.

The type, decoration and indeed quality of these medieval cotton textiles were varied. Some of the pieces, excavated in he 1980s, were directly printed using small blocks that appear to have imitated Chinese seals.

Other textiles were resist-dyed with wax and have a lightly coloured design on a darker ground. There were also examples of block printed textiles, some of which have a design of stylised animals and birds on either side of a tree, a traditional design associated with the tree-of-life.

1. Introduction

For thousands of years individual textiles, huge bales of cloth, not to mention people wearing clothes and carrying textiles moved around the world. They travelled in all directions, literally north, south, east and west and everywhere in-between!

Sometimes this movement was voluntary in the form of trade or pilgrimage, on other occasions it was forced, as in the deliberate exile and movement of specific ethnic and cultural groups and craftsmen and women. All of these travels have added to an enormous pool of techniques and skills that make a piece of cloth or a garment, and as a result every textile may entail a long story of travel and development.

The on-line exhibition Textile Travels looks at some textiles with stories of complicated travels . They are told more or less in chronological order and begin with medieval Indian textiles that were exported to the west as part of a much bigger trade in textiles, thousands of years old, that led from the Indian sub-continent to China, Indonesia, Central Asia, Iran, Africa, the Middle East, as well as the Mediterranean and Europe.

The seventeenth century saw many changes in the world, when European trade, and with it military and political power expanded rapidly. This story is reflected in the development of the Madras cotton industry in southeastern India and the British trade in so-called George textiles from Madras, that are also known in Holland as Madras-stof, still popular in West Africa and the West Indies.

Another significant development in the Indian-African textile trade took place in the late 19th century when wrap-around cloths for women were printed and exported from India. These became known as kangas and are now mainly locally produced in Kenya and Tanzania for the East African market. They are characterised by the presence of a saying in Swahili that reflects daily feelings and events.

Feelings and events are also reflected in another group of textiles, namely the so-called Wax Hollandais prints. These textiles are based on Indonesian resist-dyed batik techniques, and they were imitated from the mid-19th century by the Vlisco company in Helmond, the Netherlands and became (and still are) an important and prestigious type of printed textile found in West and Central Africa. They have since been copied by numerous printing companies in Africa, Asia, as well as Europe.

There is an imitation Wax Hollandais that was bought in the late 20th century in Nigeria. The cloth may have been printed in Nigeria itself or possibly in India for the export trade with West Africa. It shows a series of long cloth rolls that reflect the production process of tie-and-dye leheriya cloth from Rajasthan, India. The cloth has a selvedge text that states: VERITABLE REAL WAX 2181", in imitation of Vlisco labels.

Wax print from Nigeria, showing the rolled up cloths of Rajasthani resist-dyed leheriya textiles (TRC 2022.2322).

Wax print from Nigeria, showing the rolled up cloths of Rajasthani resist-dyed leheriya textiles (TRC 2022.2322).

Finally, a related story is that of bazin cloth very popular in West Africa, especially in countries such as Ghana, Mali and Sierra Leone. Bazin is a damask cotton cloth made in Europe (the best is said to come from Austria), which is sometimes dyed using West African resist techniques, while others are produced and printed elsewhere, including China.

8. Paisley for all

One of the features of the paisley motif is its versatility. It can be worn on any occasion and in any place or occupation. It can also come in a wide variety of forms, as embroidery, lace, as a beaded ornament. It can be printed and woven.

The paisley motif can be found on many forms of dress, from baby garments and Christening robes, to adult garments including swimwear (trunks, swimming costumes and bikinis), sportswear (including women’s weight lifting gloves and the costume of the Azerbaijan Olympic team of 2010), through to casual wear as well as items of high fashion. And not forgetting accessories such as bags, handkerchiefs, and, of course, corona virus facemasks.

Famous figures such as Chuck Berry, Cliff Richard and David Bowie have worn paisley, while designers and designer firms such as Yves Saint Laurent, Burberry, Gucci and Dolce & Gabbana, as well as well-known textile groups such as Liberty’s of London, have all produced ranges of paisley fabrics.

In Italy, for example, during the 1950’s and 1960’s, the Italian designer Emilio Pucci created a successful print called cachemire siciliano, which mixed symbols of Sicily with the paisley motif. In addition, in the 1980’s the Italian fashion brand ETRO made the paisley pattern into its iconic motif and it remains widely used by them to the present day, especially in Italian prêt-à-porter.

A small selection of modern gentlemen's ties with paisley motifs from the TRC collection. Please click on the image for more details.

Paisley for men

The wearing of paisley decorated garments by men literally ranges from their socks, underwear, trousers, shirts, handkerchiefs to pochettes and neckwear. Since the early 19th century, the paisley motif has appeared on scarves, cravats, ties and bowties. There are elegant forms as well as ‘loud in the face’ forms. The American businessman, Jim Thompson (1906-1967), made paisley silk ties into a feature of his silk works in Thailand and wearing a Jim Thompson tie in parts of Asia was regarded by some as a mark of wealth and connoisseurship.

A totally different form of neck- and headwear are bandanas. These are large squares of cotton cloth with a printed design of some kind. They are often associated with cowboys, but their history dates back to the late 18th century. When bandanas started to include the paisley motif is not clear, but it is likely to have been in the early 19th century when the paisley shawls were beginning to gain in popularity.

Bandanas are now also being worn by a wide variety of men and women, including country and western singers, motor bike riders (bikers), as well as gang members, with different fractions wearing, for example, red or blue paisley bandanas. Some of the bandanas include mixed paisley motifs and skulls.

Paisley for women

Paisley for women

Although paisley is mostly associated with 19th century women’s shawls, the use of paisley in women’s clothing is much wider. In the 19th century, for example, woven paisley cloth was used for bodices, jackets as well as skirts and aprons. The motif also occurred on ribbons, bands and lace.

Dresses, blouses, skirts, trousers and beachwear, using cloth with paisley motifs, were popular in the 1900’s through to the present day. It also occurs on virtually everything, from underwear to stockings, as well as on accessories such as gloves, hats and shoes.

As the fashions in materials, designs, colours, style and cut of women’s dresses changed over the last century, so did the appearance of the paisley motif. There is a big difference between a 1930’s paisley dress, and one of the 1950’s and 1960’s. From the 1960’s onwards there was also a growing difference between formal and informal wear, as well as urban versus folkloristic (bohemian) styles of garments. These are trends and fashions that are reflected in the form of the paisley motif used.

Steampunk gothic

Steampunk is a ‘retrofuturistic’ fictional genre and a form of cult clothing that developed in the late 1980’s. It is based on the concept of 19th century industrial and steam powered technology, mixed in with modern science fiction and horror. The associated fashion scene is a mixture of 19th century retro-fashion and fantasy. Not surprisingly, paisley is a popular motif of this group and is worn by both men and women.

Paisley is for everyone!

7. Some Western paisley variations

Over the centuries, various forms of the paisley motif have developed in the West. In particular throughout the 20th century, the paisley motif has been creatively transformed accordingly to the contemporary fashion and style of printing.

These patterns include small concise forms (early 19th century), large elongated versions (19th and early 20th century), floral forms (1930’s), abstract blobs (1950’s), negative shapes (1960’s), even an atomic version (1960’s) and op-art versions (1960’s-1970’s). There are also ‘animated’ versions, which include elephants or fish (1980’s). There are even designs that mix paisley motifs with rats (designed by Patrick Moriarty in c. 2017). Basically, the development of the paisley motif will continue with every change in fashion.

Indian and other motifs mistaken for paisley

john L and his Phantom V Rolls Royce, NOT with paisley motifs.Sometimes Indian and some types of European floral designs are mis-identified as paisley motifs. This can be seen on garments such as a kaftan from Singapore, which includes a variety of ornate ‘oriental’ foliate motifs. Another classic mistake is the often cited Rolls-Royce owned by former Beatle, John Lennon, in the 1960’s, which is often said to have included paisley motifs. The car is decorated with European scrolling foliage, but not the paisley motif!

john L and his Phantom V Rolls Royce, NOT with paisley motifs.Sometimes Indian and some types of European floral designs are mis-identified as paisley motifs. This can be seen on garments such as a kaftan from Singapore, which includes a variety of ornate ‘oriental’ foliate motifs. Another classic mistake is the often cited Rolls-Royce owned by former Beatle, John Lennon, in the 1960’s, which is often said to have included paisley motifs. The car is decorated with European scrolling foliage, but not the paisley motif!

Most of the samples below are taken from the collection made by the French artist and designer, Professor Yves Cuvelier (1913-2005), part of which was donated to the TRC. For more information, see a TRC blog, 'A glimpse into the post-war Parisian textile world', 28 March 2020.

6. Paisley and European regional textiles and dress

Given the popularity of the motif it is not surprising that it can be found on various forms of European regional dress. It occurs on Russian headcoverings and shawls for the babushka (‘grannies’), and on incidental garments in Scandinavia, Germany and the Netherlands. It is a popular motif among the garments worn by women on the Dutch island of Marken, and occurs in both children’s and women’s garments. Paisley motifs can also be found on some women’s bodices from Staphorst, also in the Netherlands.

Paisley features prominently among the regional dress of the island of Kihnu in Estonia. In particular, it is used for the aprons, jackets and headscarves worn by the women.

There has been considerable attention over the years for a typical type of Indian cloth generally called chintz (sits in Dutch), its European copies, and the popularity of these textiles in Europe in the 18th and 19th century. There is a specific form of these textiles that is still alive in southern France. It is known as tissu de Provence, tissu Indienne, tissu provençal, cotonnade provençale, or, briefly, simply Indienne. The production of these textiles, which still continues, is based on 17th and 18th century cotton chintz textiles that were initially exported from India to France and then copied in various southern French towns, notably Avignon, Marseille, Mulhouse and Rouen.

The designs used for Indienne have changed over the centuries and may include both Indian based motifs as well as ones that are designed to appeal to local people and tourists. European influence can be seen in the Regency style examples, which use broad bands or ‘ribbons’ in a single colour, alternating with small, sometimes chintz-like motifs. But the buteh is still an often recurring motif in these ‘Indian’ textiles from southern France.

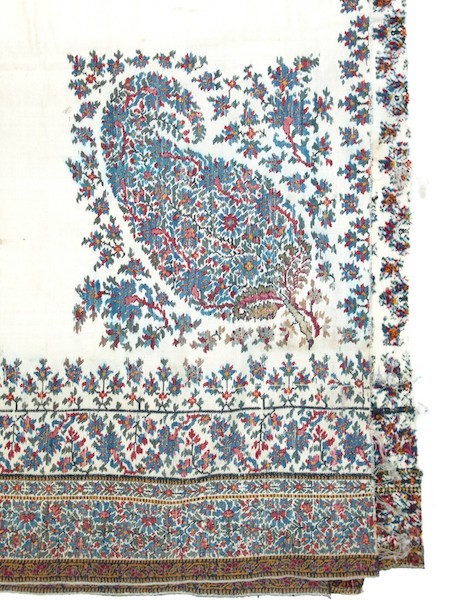

5. Kashmir and paisley shawls

The paisley shawl originates in Kashmir, India, and in particular among the shawls being woven and sometimes also embroidered in the 18th century for the Mughal court of India and related elite groups. In the late-18th century, more and more of these shawls were being exported to Europe. They became very popular at various royal courts. Joséphine de Beauharnais, wife of Napoleon Bonaparte, for example, is said to have owned over 200 of these shawls.

By the beginning of the 19th century Kashmir-style shawls started to be copied on hand and later on mechanical looms, especially the Jacquard loom, in France and Britain. Although in Europe they never managed to mechanically reproduce the striking number of colour combinations of the original Kashmir shawls. One town in particular became noted for the production of ‘Kashmir’ shawls, namely Paisley, which lies just south of Glasgow (Scotland).

From the early 19th century, Paisley was an important producer of shawls for domestic and export purposes. By 1850, for example, there were over 7,000 weavers producing shawls. In addition, special versions of the ‘Kashmir’ shawl were being produced in Paisley and elsewhere in northern Europe that consisted of different pieces of the shawl being woven on machines and then being stitched together.

In addition, the motif began to appear on other garments, such as women’s bodices, jackets and skirts. The popularity of the paisley shawl started to decline in the 1870’s, following a change in fashion (especially the advent of the bustle, which meant that the shawls could not be draped to their best advantage), and at the same time shawls had become too ‘common’.

Dutch worteldoeken

In the 19th century Dutch manufacturers started to produce shawls and other items with a double weave design of flowers, leaves, and of course, paisley motifs. The Dutch version is much thicker than the French and British versions and regarded as much more hard wearing.

There are various suggestions why they are called worteldoek (‘carrot cloth’) - some say it is due to their predominantly orange colour, others that sometimes these cloths were used for carrying and storing root vegetables including carrots, but the most likely explanation is that the paisley motif looks a little like a carrot.

Renfrewshire Council logo. The town of Paisley lies in Renfrewshire.This type of cloth was not just used as a shawl. They were also used to cover pianos, on mantle pieces, as well as protecting garments against damage from walls by hanging the cloth behind a coat rack.

Renfrewshire Council logo. The town of Paisley lies in Renfrewshire.This type of cloth was not just used as a shawl. They were also used to cover pianos, on mantle pieces, as well as protecting garments against damage from walls by hanging the cloth behind a coat rack.

Renfrew tear drop

The Renfrewshire Council (which includes the town of Paisley) uses a double version of what they called the ‘Paisley tear drop’ as their logo.

4. The world of paisley

The spread of the paisley/buteh motif around the world is closely connected with the vast trade in textiles from India which has been carried out for at least 2,000 years. From India the paisley/buteh motif has spread to countries as far apart as Ghana in West Africa and Japan in East Asia. In the 19th and 20th century, the production of paisley/butehtextiles (mainly woven and printed forms) in Europe, as well as India, was well developed, although by the end of the 20th century much cheaper items from China had taken over much of the market. Yet throughout these centuries the popularity of the paisley motif has not declined. If anything, it has become more diverse and became incorporated into the design heritage of many cultures.

The paisley motif and Southwest Asia

The use of the paisley/buteh motif started in Iran and became very popular in India, so it is not surprising that it remained popular in these and neighbouring countries. There are numerous examples of 19th century Qajar paintings from Iran, for instance, which include depictions of members of the various royal courts wearing garments with the paisley motif. In addition, household items such as prayer mats, wall hangings and towels, were often decorated with the buteh.

The paisley/buteh motif could also be found in Afghanistan and Central Asia and again it was popular for both men and women’s clothing. In particular it was used for headwear and items such as jackets and coats.

The paisley motif and Southeast Asia

The paisley motif appears to have arrived in East and Southeast Asia by at least the 19th century and came mainly via Indian textiles. It has remained a feature of various East and Southeast Asian countries, notably Japan and Indonesia. For some reason, while known in countries such as China, Malaysia and Thailand, it was not as popular as elsewhere.

The paisley motif has been popular in Japan for at least 200 years. It is known as the skoukyumoyo or pinecone pattern. It appears to have been introduced by European and Indian merchants, especially those dealing in textiles and garments. It is regarded by the Japanese as being a typically British, or Scottish pattern. The paisley motif is now used for a variety of garments, including the kimono and obi (sash). In some cases, the motifs are small and discreet, on other occasions they may be large and loud.

Indonesia

For several hundred years, the paisley/buteh motif has been a popular form in Indonesia, especially in Java. It can be found mainly on batiks and takes on ornate forms. In Indonesia the buteh has become very popular among the Indian community. With the recent resurgence of Islam, wearing the buteh motif declined as it was seen as a Hindu motif, although, ironically, it originally derived from Iran, a Muslim country.

The paisley motif, Turkey and the Middle East

The paisley motif can be found in both Turkey and the Middle East. In particular, it was popular in Turkey during the 19th century and later, and it has survived in various parts of the country as part of regional dress, notably as decoration on headscarves and the resist-dyed aprons in eastern Anatolia.

In contrast to many other regions, the motif does not appear to have been so popular in the Arab Middle East. This may be due to a preference for geometric, rather than ‘organic’ designs. The paisley motif does occur, but it tends to be mainly in areas where there has been a strong European influence, such as in Algeria, Egypt and Lebanon, which had access to imported European materials, ribbons and bands.

The paisley motif and Africa

The paisley motif can be found on a variety of African objects, including the wrap-around garments for women known as kanga in East Africa, as well as on printed women’s headwear in West Africa. Many of these pieces used to be made in Europe and western India for the local markets, but more and more are being made in China. Sometimes these textiles have a mixed Chinese/African feel to the designs! As a result, sometimes the paisley motif can take on a more Chinese yin-yang design.

3. History of the paisley motif

There are various theories about the early history of the paisley/buteh motif. It would appear that it originated in Iran during the early first millennium AD. At this date it was a bulbous, almond shaped form, which was often flowery, and more significantly, without a very prominent hook (right). In general, the motif was placed as an isolated bush, as flowers or sprigs, on a plain ground. This motif is specifically known as a buteh.

This form of the motif was used during the Sassanian period (224-651 AD) in architecture, on tiles, as well as on silk textiles. By the 9th century the motif can be found in various parts of the Iranian plateau, including Afghanistan, notably among the reliefs (left) in the Noh-Gumbad (Masjid-i Haji Piyadah) mosque in Balkh, in northern Afghanistan.

By the late Safavid period (1501-1736) the motif had evolved in Iran from the floral form into its more recognisable (modern) shape with a hook. This version of the buteh spread widely throughout the Iranian plateau and elsewhere. Technically the hooked variation of the motif is known as the kalga or kalga buteh, but nowadays it is generally simply called by the same term as the earlier version, namely the buteh.

At the same time, the motif travelled from India to Europe and especially Britain, as well as eastwards to Indonesia. And in doing so it became a global motif. In the late eighteenth century, the buteh/ kalga became even more popular as it was featured on the hand woven and sometimes also embroidered Kashmir shawls that were being exported in vast quantities to Europe and there copied on an industrial scale for the growing demand for this product.