Gillian Vogelsang-Eastwood, 10 March 2024

A gentle day (9th March) in London visiting some very different venues! As part of looking at exhibitions and other displays, Willem and I went to three venues today. The first was St. Paul’s Cathedral, the second Apsley House, the stately home of the Duke of Wellington who defeated Napoleon in 1815, and the third was the King's Gallery (the former Queen’s Gallery), Buckingham Palace.

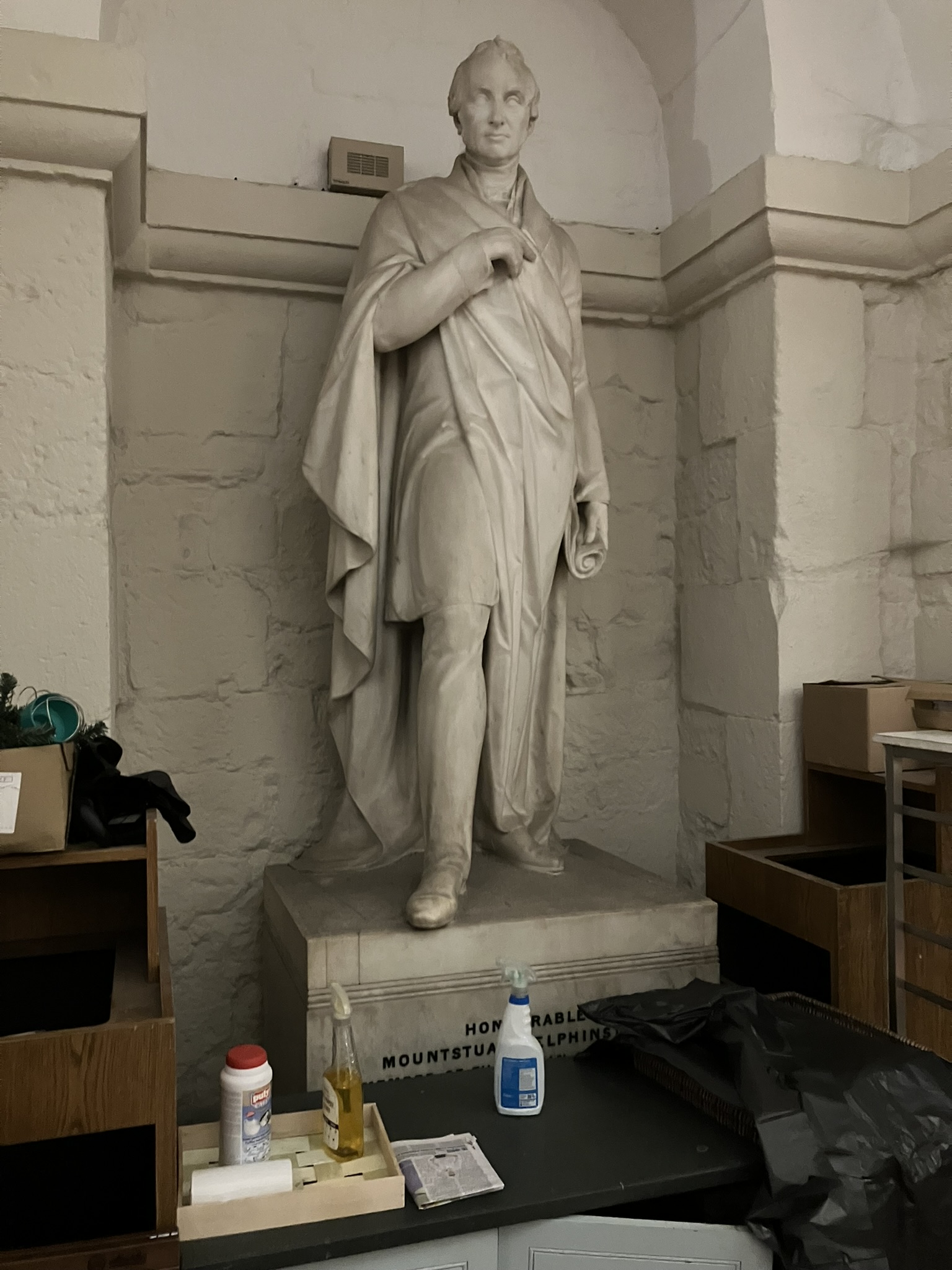

Statue of Mountstuart Elphinstone, in the crypt of St. Paul's, London. Photograph Willem Vogelsang.On the ground floor, the grand cathedral of St. Paul’s has become a commercial institute with a couple of small chapels for those who want to pray, but visitors have to pay for the honour of being there, and it feels like it. But there are some interesting items, such as the very grand and elaborate memorial to the Duke of Wellington!

Statue of Mountstuart Elphinstone, in the crypt of St. Paul's, London. Photograph Willem Vogelsang.On the ground floor, the grand cathedral of St. Paul’s has become a commercial institute with a couple of small chapels for those who want to pray, but visitors have to pay for the honour of being there, and it feels like it. But there are some interesting items, such as the very grand and elaborate memorial to the Duke of Wellington!

However, going down into the Crypt is stepping into British history, as there are the graves and memorials to Sir Christopher Wren, Sir Isaac Newton, Florence Nightingale, Montgomery of El Alamein as well as many artists and poets including Blake, Millais and Turner. The 18th century memorials are subdued, the 19th century ones are not.

We were there to see the monument to Mountstuart Elphinstone (1779-1859), a man who in 1815 published a book on Afghanistan (An Account of the Kingdom of Caubul ....), which is still widely read and quoted to the present day. He was a very famous man in his days. He refused the position of Governor General of British India, but instead set up educational centres in Mumbai (Bombay) and wrote a History of India. We found him, literally a larger than life marble statue wearing a draped cloak, in the workroom area of the Crypt café, surrounded by cleaning equipment. Sic transit gloria mundi.

I should like to add a note of thanks to the St Paul’s staff, who were fantastic in helping us find the Elphinstone memorial. It was the first time anyone had ever asked where he was and they were intrigued about his story.

Sir William Elphinstone, centre, in red jacket. Detail of a large painting of state banquet at Apsley House.Then onto Apsley House, the London home of the Duke of Wellington (and his descendants). What a treasure house of paintings! We were initially there looking for another Elphinstone link, as there is a painting that includes a relative of Mounstuart (William Elphinstone, 1782-1842), who saw service under Wellington, and who many years later led the British troops in Kabul to utter disaster in the winter of 1842 (he died between Kabul and Jalalabad), and who was last year voted the worst general in British military history.

Sir William Elphinstone, centre, in red jacket. Detail of a large painting of state banquet at Apsley House.Then onto Apsley House, the London home of the Duke of Wellington (and his descendants). What a treasure house of paintings! We were initially there looking for another Elphinstone link, as there is a painting that includes a relative of Mounstuart (William Elphinstone, 1782-1842), who saw service under Wellington, and who many years later led the British troops in Kabul to utter disaster in the winter of 1842 (he died between Kabul and Jalalabad), and who was last year voted the worst general in British military history.

He is included in a painting by William Salter of a state banquet with the Duke of Wellington (1836), with other military men (no women were allowed to sit at the table). There seem to be more men than chairs. Photoshopping is nothing new!

Coronation robes of the Duke of Wellington, worn at the coronation of George IV. Apsley House. Photograph Willem Vogelsang.What we also saw at Apsley House were the coronation robes of Wellington and his sons, which were worn at the coronation of George IV in 1821. They had been put on display to celebrate the coronation of Charles III in 2023. All the garments were deliberately 16th /17th century in style, something apparently the duke found silly, but effective in getting the public behind the ceremony.

Coronation robes of the Duke of Wellington, worn at the coronation of George IV. Apsley House. Photograph Willem Vogelsang.What we also saw at Apsley House were the coronation robes of Wellington and his sons, which were worn at the coronation of George IV in 1821. They had been put on display to celebrate the coronation of Charles III in 2023. All the garments were deliberately 16th /17th century in style, something apparently the duke found silly, but effective in getting the public behind the ceremony.

The many paintings on display in Apsley House were fascinating, ranging from work by Jan Steen (yes, from Leiden), and van Dyke, and many emphasised the garments and textiles being worn and presented, from the clothing of a milkmaid to the civilian and military uniforms associated with the Duke himself. There were also Field Marshal batons, some of which had gold embroidered shafts; a new use, at least for me, of embroidery. There was also a painting of a young woman wearing a full skirt and apron that partially hid a chatelaine. I am intrigued by this item of female status and the related sewing skills.

Coronation robes of one of sons of the Duke of Wellington. Coronation of George IV, 1821. Photograph Willem Vogelsang.We then had a short walk to Buckingham Palace and we did an element of clothing watching, because thousands of people were coming together for the 10th pro-Palestinian demonstration. I was fascinated by the many different ways people wore the kaffiyeh (a black and white head covering originally from Jordan and now associated with the Palestinian cause) and the Palestinian flag. Dress and identity in action; the political use of dress, a subject for another day.

Coronation robes of one of sons of the Duke of Wellington. Coronation of George IV, 1821. Photograph Willem Vogelsang.We then had a short walk to Buckingham Palace and we did an element of clothing watching, because thousands of people were coming together for the 10th pro-Palestinian demonstration. I was fascinated by the many different ways people wore the kaffiyeh (a black and white head covering originally from Jordan and now associated with the Palestinian cause) and the Palestinian flag. Dress and identity in action; the political use of dress, a subject for another day.

But back to paintings. Yesterday in the Sargent and Fashion exhibition at the Tate Britain, I noted that here was an artist who understood and could convey the texture of textiles and garments. In the King's Gallery we saw another artist who could do this, namely Hans Holbein (c. 1497-1543). He was a Swiss-German artist who worked in London and elsewhere.

The exhibition was called ‘Holbein at the Tudor Court” and contained many sketches and preliminary drawings for paintings, such as those of the royal family as well as other important groups, including the Howard family (two of whom were married to the king and they were later executed on his orders), as well as that of Thomas Moore (Sir Thomas Moore was also later beheaded at the instigation of the king). The attention to detail with regards the headdresses worn by Sir Thomas Moore’s daughters was intriguing.

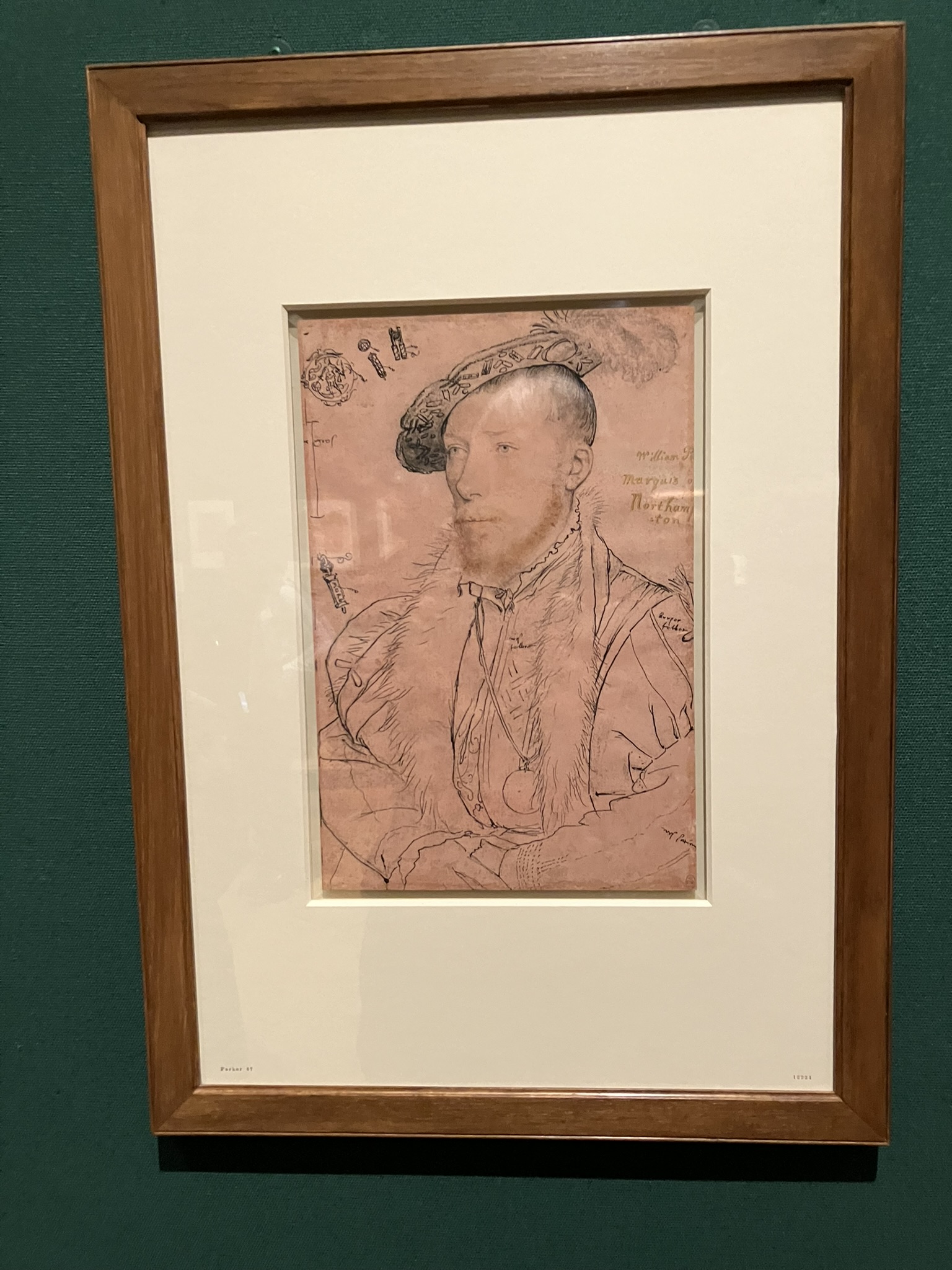

The Marquess of Northampton (1513-1571), by Hans Holbein (1540). Royal Collection.But this observation could be applied to many of the other items on display. One sketch in particular caught my eye, which was for the Marquess of Northampton, with written notes about the velvet, and detailed precise sketches of the jewellery on the man’s headwear.

The Marquess of Northampton (1513-1571), by Hans Holbein (1540). Royal Collection.But this observation could be applied to many of the other items on display. One sketch in particular caught my eye, which was for the Marquess of Northampton, with written notes about the velvet, and detailed precise sketches of the jewellery on the man’s headwear.

Holbein painted woven textiles, especially brocades with gold coloured threads, and he caught the stiffness and complexity of the material. It comes back to skill, experience and the ability to catch reality and to use these to create an image the viewer can relate to and understand, even after a gap of over 500 years.

These various exhibitions confirmed an idea I have had for some time, namely of going through a suitable painting collection and adding more information about the garments being worn, and wouldn’t it be interesting to study the embroidery and/or lace and put actual examples next to the painted versions. Maybe next year…..